This post was originally published on Athlon Outdoors.

As the Empire of Japan prepared for an expected invasion of its home islands 80 years ago, it began to develop so-called “last-ditch weapons.” These were intended for civilian militias and hastily raised military units. Such weapons included simplified versions of small-arms worked over in decentralized workshops and factories. Keep in mind that firearm historians would point out that Japan’s military weapons were already crude at that stage in the war. It’s not unlike Kreigsmodell German Mauser K98k rifles produced in the final months of the Third Reich.

Yet, there is another part of this story.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Japanese firearms were largely perceived as inferior compared to Allied armament. Several factors contributed to this perception. Ironically the island-nation of Japan carries a modern reputation for its love of advanced gizmos and gadgets. However, during the during, before and after the Second World War, Japan’s situation was very different.

Fighting the Last War

After its famous centuries-long isolation, Japan managed to take a prominent place on the world stage by the early 20th century. This process only took a few short and speedy decades. Japan managed to defeat China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). It then gained control over Korea and Taiwan. Not long after that, Japan managed to beat Imperial Russia too.

The Empire of Japan was among the Allied powers during the First World War, where its forces overran Germany’s colonies in China and the Pacific quickly. This led to Japan becoming a world power. More so, the island nation’s ease of victory and a significant recession in 1926, helped give rise to Japan’s militaristic streak that ultimately led it to clash with Western powers in World War Two.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

It once again became isolated, at least militarily, from the rest of the world.

Since Japan was spared the horrors of European trench warfare in WW1, it also failed to update its infantry tactics and its military equipment. Some even thought that Japanese soldiers essentially fought World War Two with First World War weapons and gear.

But this is only partially true.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

By the time the Second World War began, Japan’s main infantry rifle still consisted of the same type of standard bolt-action rifle that was in use a generation earlier. It’s not fair to single out the Japanese Empire for this because the same was true of other major powers. But Axis and Allies alike, whether it was the Soviets, Germans, British Commonwealth, etc, many of these nations had made significant efforts to modernize their gear and tactics. Japan did the opposite. If anything, Japanese workmanship diminshed as the war progressed.

Blades & Traditions

It’s not even that Japanese firearms were low quality, at least not until much later in the war. But it’s fair to point out that some of these Japanese-designed guns had design flaws from the start. Considering that the Imperial Japanese Navy succeeded in adopting an aircraft carrier doctrine while also building the most potent class of battleships the world had ever seen, it’s another irony.

It was clear that the priority wasn’t in the equipment and weapons issued to individual soldiers. If it already worked, the Japanese leadership saw no need in upgrading it.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

It’s also important to consider that much of Japan’s infantry doctrine was tied to the Bushido code, the ancient samurai “Way Of The Warrior.” Bushido saw surrender as an unacceptable outcome. Japan also had a strong sense of loyalty to its emperor. This fervency served to further enhance the Japanese fighting spirit. Throughout much of the war, surrender wasn’t seen as an option. It would be too shameful. The same even held to the concept of retreating, and as a result, many a Japanese life was wasted over a matter of honor, even as the situation turned hopeless.

On top of everything else, Japan’s martial traditions were centered around blades. Japanese swords were like steel bibles of sorts. Carrying swords was a considered a huge deal, and only something that officers typically did. Furthermore nearly every firearm in Japan’s wartime arsenal had the means to attach a bayonet. It wasn’t just infantry rifles, but even actual machine guns.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Why worry about small improvements in guns when honor and steel mattered more?

Japan’s Last Guns Of Empire

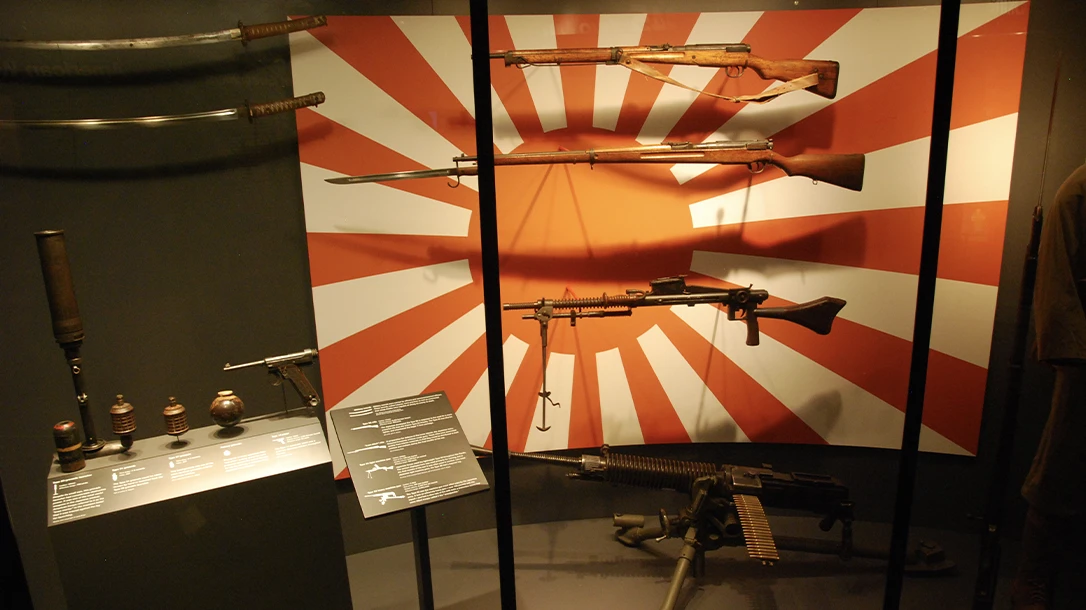

Arisaka Type 38 & Type 99 Rifles

Both of the Japanese military’s bolt-action rifles were known as Arisakas. The name comes from Colonel Nariakira Ariska, who oversaw the commission to find a new rifle. Beyond that, their nomenclature can become a little confusing. Readers can appreciate that all Arisaka rifles were influenced by the pervasive Masuer-style action.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The very first Arisaka bolt-action variant was known as the Type 30. It denoted the 30th year of Emperor Meiji’s reign (1897 A.D.) Not long after, the upgraded Type 38 bolt-action rifle came on scene. Both variants fired the Japanese 6.5×50 Arisaka Semi-Rimmed cartridge. Throughout their service life, more than three million were made. The Type 38 rifle was simplistic in design and operation, and remained in use through the war’s end.

Following Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Japanese military saw the need for a larger cartridge. It soon adopted the 7.7x58mm round, based off .303 British but without the rim. Confusing collectors and military historians for decades, this rifle was designated the Type 99. This number refers to the Japanese year 2099, a date believed to follow the creation of the world.

Approximately three and a half million Type 99 rifles were manufactured, excluding variations such as sniper configurations and take-down models, which were reportedly designed for use by paratroopers. Another version of the rifle, the Type 44 Carbine, was intended primarily for use as a cavalry rifle. However, this shouldn’t be confused with the Type 38 Cavalry rifle, a slightly shorter version of the Type 38. In total, approximately 3.5 million Type 99s were produced at nine different arsenals, including seven arsenals in Japan, and the other two located in Mukden, Manchukuo, and Jinsen, Korea.

Type 11 Light Machine Gun

Japanese gun designer Kijiro Nambu was sometimes considered the “John Browning of Japan.” But that’s honestly an insult to Browning. Nambu is noted for being a prolific Japanese designer. He is credited with more than a dozen designs. Nambu is well-known for his series of 8mm Nambu pistols, including the infamous Type 94 pistol. (This one is notable for being dangerous to both the user and his enemy).

Pistols aside, his true “masterpiece” [sarcasm meter 9000] was the Type 11 light machine gun. This Japanese LMG is modeled after the French Hotchkiss air-cooled, gas-operated light machine gun from WWI. Nambu attempted to “improve it” with some of the most questionable changes.

Instead of a traditional box magazine or ammunition belts, The Type 11 fed from a hopper that was charged with the same stripper clips used to the Type 38 bolt-action rifle. The clips were loaded into a detachable hopper, allowing the gun to be constantly fed with ammunition while firing.

In theory, this seemed like an excellent idea. By early light machine gun standards, it even made sense in its own way. Soldiers in the same squad could share ammunition with the machine-gunner by “donating” rifle ammo already in the same clips. In practice, it caused numerous problems. Dirt and grime easily found their way into the hopper to jam the weapon. Type 11s also relied on an oiler to lubricate ammunition while feeding. Nothing makes dirt stick the way oil does. Making things worse, the hopper threw the Type 11’s balance off center. To correct this, Nambu compensated for the issue by bending the stocks and sights to the right.

The Type 11 worked in perfect conditions, but it was 1920s emerging machine-gun technology at best.

Type 92 Heavy Machine Gun

Nambu also designed the Type 92 heavy machine gun. Like the Type 11, the Type 92 is also based on the Hotchkiss. Type 92s fired 7.7 mm Shiki rounds at approximately 2,400 feet per second with a rate of fire of just 450 rounds per minute. This rate of fire was slower than contemporary HMGs of the era. It even earned the nickname the “woodpecker” due to the distinctive clicking sound it made while being fired. The gun had a maximum range of 4,500 meters, but the realistic range was about 800 meters. It could be transported in a forward advance by carrying the entire HMG on its tripod, via removable carry poles.

That also likely seemed practical, but the crew had extra gear, namely the poles, to lug around. Even worse, as it was fired by an extended length brass clip that held 30 rounds. Because it was a Hotchkiss design, the cases had to be lubricated due to the violent and swift extraction. But again the issue lies in the fact that oil attracts dirt and sand.

On the bright side, its heavy weight and slow rate of fire made for a very accurate and controllable machine-gun. Type 92s could also accept rudimentary 4x optical sights. When placed in well-concealed defensive positions, these guns could be quite threatening despite some of their other drawbacks.

Type 96/Type 99 Light Machine Gun

These two light machine guns were arguably Nambu’s most successful designs. But like many other Japanese firearms of the era, some credit must go to earlier European designs. In this case, the Czechoslovak ZB vz. 26 machine gun–the basis of the Type 96. The same Czech design also inspired the famous British Bren Gun. It’s not hard to see the similarities between all three models. The top-mounted curved magazine is perhaps the most recognizable feature found in this trio.

The biggest problem with the Type 96 is that it was prone to jamming with stuck cases. To solve the problem, Nambu suggested that the cartridges should, yes, you guessed it, be oiled – his go-to solution for any machine-gun problem.

The Type 96 was refined as the Type 99. For reasons that seemed practical at the time, early models were fitted with a rear monopod to raise the weapon off the ground. Thanks to Japan’s martial blade culture and that previously mentioned Bushido influence, these light machine guns could be outfitted with a bayonet.

To its credit, the Type 99 also incorporates one of the best features from the vz.26 and Bren: a removable barrel. Such barrels are practically mandatory for serious military machine guns in order to address overheating.

Type 100 Submachine Gun

The Japanese experimented with SMGs, and that included the Type 2, a firearm that was quite forward-thinking as it was the first small machine pistol to have the magazine clip extend from the pistol grip. However, it was only produced in small numbers near the end of the war.

The far more “common,” yet still rare compared to the Thompson, was the Type 100. Another Nambu design, it was introduced in 1942, which is odd considering Tokyo had sought to produce a licensed copy of the German MP18/Swiss SIG Bergman from 1920. It is unclear why that didn’t move forward, but instead Japan called up Nambu to develop an “original design.”

By the end of WWII, only 30,000 Type 100s were produced. These numbers paled in comparison to the quantities of German, Soviet, British and American SMGs used throughout the war.

Mechanically, the Type 100 was simple and straightforward. It cycled 8×22 mm Nambu pistol cartridges and fired from a straight blowback open bolt. Again, as with the rest of Japan’s small-arms, it’s hard to deny European influence. Type 100s nearly resemble the original German MP-18 SMG from WWI, down to the left-side magazine. Among the most noteworthy elements were the curved magazine and chrome-plated bore. Some early models also featured a bipod, although the practicality of this feature is debatable. And yes, the Type 100 could also accept a Japanese bayonet.

Type 100 SMGs are amongst the rarest WWII SMGs. So few were made, and even less survived the war and are still intact. Morphy Auctions sold a Type 100 last year for $84,000! That might be the most lavish praise Nambu could receive.

The post Japan’s Wartime Weaponry appeared first on Athlon Outdoors Exclusive Firearm Updates, Reviews & News.